All posts by crit

Video: Race and Crime

Video: State Crime

Video: Green Criminology

Video: Cultural Criminology

Video: Peacemaking

Video: Restorative Justice

Video: Feminist Criminology

Video: New Directions in Critical Criminology

Red Feather

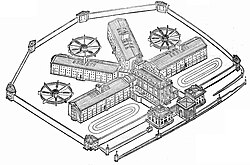

Red Feather Institute for Advanced Studies in Sociology

T. R. Young was the director of the Red Feather Institute for Advanced Studies in Sociology. His website, which included many critical criminology pages and one of the first online journals, was one of the earliest criminal justice sites on the Internet – which at that time meant it was one of the only online criminal justice sites. While his site disappeared shortly after his death, critical criminologists wanted to retain this archive.

T. R.’s family graciously agreed to allow these pages to be hosted at critcrim.org. The original pages are linked below. Some images are missing, and the html may not be 100% compatible with today’s standards, but the ideas remain relevant.

About the Red Feather Institute

The Red Feather Dictionary of Critical Social Science

to the

RED FEATHER INSTITUTE

For

Advanced Studies in Sociology

Video: Social Construction

Video: Critical Criminology

Facebook Feed

Environmental Damage Remains Widespread while Criminology Sleeps

Environment Damage Remains Widespread While Criminology Sleeps

This post addresses the neglect of green crime, victimization and justice within criminology. Other disciplines have long addressed the forms of harm destruction of the environment produces. In general, criminology overlooks these issues. Of importance to that discussion is addressing the ecological destruction capitalism produces, and which it must produce, to fulfill its accumulative goals.

Michael J. Lynch

Department of Criminology

Associate Faculty, The Patel School of Global Sustainability

University of South Florida

Tampa, Florida

Criminologists have failed to adequately address the scope of green crimes and the diverse forms of victimization green crimes present in contemporary society. To be sure, green crimes are not simply a modern problem, and scientists have long commented on the environmental problems that face society. The field of environmental toxicology, which can be traced to the influential work of Rachel Carson in the early 1960s formed the basis for the modern era of concern with ecological damage. Medical studies in occupational and public health which can be traced to the 1830s, and well known studies of the effect of poor environmental conditions on the health of the working class (by Charles Turner Thackrah (1831), Edwin Chadwick (1842), Rudolf Virchow (1848) and even Frederick Engels’s (1845) analysis of the conditions of the English working class; for general discussion see, Herbert K. Abrahams, “A Short History of Occupational Health,” 2001, Journal of Public Health Policy, 22,1) mark the earliest acknowledgements that environmental pollution of workplaces, neighborhoods and homes caused physical damage. Yet, in the interdisciplinary field of criminology, the scholarly work on such issues remains untouched, and the issues of green crime and justice largely ignored.

While the average academic criminologist spends a great deal of time and effort attempting to explain why the marginalized mass of the population is the most prone to commit street crime (as if being marginalized was insufficient for this purpose), and in pursuing those explanations invents dozens of individual level explanations for those crimes that explain very little individual level variation in crime; and while the “more radical” among them seek out the cultural meaning of crime and the subjective, individual aspects of the construction of crime as an expressive act – there are real dangers building themselves to staggering new heights all around us. These are the green or environmental crimes of our times, which worsen daily as they build on their own past, destructive history, accumulating daily, filling graveyards and hospitals and doctors’ offices with its victims and lists of extinct and endangered species with some of its nonhuman species. Yet, these green crimes, which harm the living system of earth, its subsystems, and all of the various species that inhabit the living earth – the green crimes which endlessly victimize the living earth and all its species through the global march of the destructive powers of the capitalist world system of production and consumption — go unnamed by the average criminologist, neglected as if they did not exist at all, and as if they caused no harm and were unworthy subject matter. But it is these latter crimes, the green crimes of capitalist industry and the political economy of capitalism, which hide in the open as the criminologist stares around the world for some subject matter of interest to examine, that the criminologist overlooks, and which the discipline of criminology cannot fathom as an offense, that promote the greatest destructive force of our time.

This is a serious charge against criminology, and some would challenge this assumption, asking for support of these contentions. That evidence, too, lies all around us in various government reports and in the writing of a variety of scientists from numerous disciplines – but rarely criminology. The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, for example, estimates that 50,000 deaths are caused each year in the US due to poor air quality alone, and that the cost of addressing illnesses that result from exposure to air pollution costs $150 billion annually. The World Health Organization estimates that 40% of deaths world-wide are pollution related. Extending that estimate to the US, we can estimate that that there were approximately 1,000,000 deaths last year due to pollution – a figure that is more than 65 times the number of homicides that occur in the US. And while the harms from green crimes far outweigh those from street crimes such as homicide, homicide is an outcome that occupies much of the time criminologists spend on the study of crime. Thus, if we limit our analysis to just the human consequences of pollution and take a rational look at the harms around us, criminologists could make a much more important contribution to society by addressing the causes and control of pollution than they can ever make even if they were somehow to discover the causes of homicide and entirely eliminate homicides.

Criminologists have long been trained to ignore the forms of victimization caused by the powerful, which includes among those behaviors the forms of ecological damage generated by capitalist industries. Indeed, criminologists not only ignore the crimes of the powerful, they offer extensive critiques of theoretical positions that draw attention to the sources of the crimes of the powerful. Of particular relevance is the critique of radical or political economic explanations of crime, and rejection of the hypothesis that the organizational structure of capitalism plays a significant role in the development those green crimes. Having rejected that obvious association, one that is found, for example, in portions of the ecological literature, especially in economics, the criminologist cannot imagine for a moment that green crimes are a serious problem, or that the modern organization of the global capitalist world system plays a role in perpetuating green crimes. This thought is beyond the limited scope of the micro-level orientation of the typical criminologist.

Because they have rejected the theoretical relevance of political economic analysis and fail to perceive the role political economy plays in ecological destruction, the criminologist is unable to perceive the (green) crime problems that stare them in the face. The criminologist cannot appreciate the fact that the destructive force of capitalism consumes the world, and in doing so undermines the health of the ecosystem and the ability of the various life forms on earth to survive. In contrast, as radical ecologists point out (e.g., Foster, 2000; Burkett, 2006), capitalism must consume and destroy nature in order to produce commodities and to generate profit, which is, after all, the life force of capitalism (for discussion see, Dunn, 2003). Capitalism must, in order that it may live and expand and transform nature into wealth, devour nature. The criminologist, because they are unaware of this literature, fails to appreciate that capitalism consumes nature to the advantage of the few – the economically privileged — and that the consumption of nature produces unequal advantages and disadvantages for the rich and poor.

The vast majority of criminologists, unaware of this argument, fail to perceive the world as it is, and instead sit idly by in the face of ecological destruction, persistently drawing society’s attention to the impoverished offender who is, like the green crimes that threaten the existence of all the species on earth, created by capitalism’s gigantic machinery of production and consumption. In their neglect of these green crimes and their political economic origins, the average criminologist fails to appreciate what the physical scientists of the world are telling us about the state of the world’s ecological system – that it is in deep trouble (Lovelock, 2007, 2000), ailing, and on its last legs as the industrial sectors sucks the life out of the earth to manufacture goods to meet the demands for goods capitalism itself stimulates (Kovel, 2007). The average criminologist takes no notice of these things going on all around them, and cannot comprehend that there is an essential contradiction between nature in its healthy state and the expansion of capitalism, for capitalism must, by its very design, destroy nature to enlarge itself, to gorge itself on nature’s resources.

If there is any doubt that this is the case – that the modern capitalist world system creates excessive consumption — one can refer to scientific measures of this relationship between capitalism and nature. These measures include, for example, the ecological footprint of nations (see the website of the Global Footprint Network, www.footprintnetwork.org). Today, the world ecological footprint is 1.5, meaning that in a year, humans consume the volume of ecological resources nature produces through the labor it applies in 1.5 years. Anyone who understands the very basic principles of mathematics understand that this means that humans are consuming their way to extinction. Assuming that the ecological footprint effect is a simple cumulative function and that there is no feedback between excessive consumptions effects in one year on the ability of nature to reproduce itself at other points in time, and if the ecological footprint were to remain the same – and it is growing, not shrinking – then in a decade, humans will consume 15 or more years of nature’s labor; in a half century, three-quarters of a century of nature’s work, and so forth. That this measure, however, underestimates the effect on certain segments of nature should also be established. For example, nature cannot growth back a forest quickly, and it may take a century for a mature forest to begin to re-establish itself once destroyed (e.g., estimates vary by type of forest, ecosystem composition, and presence of human activities; see, Mueller et al., 2010, who estimate recovery periods of 80-260s years; others find full recovery effects of between 700 [White and Oates, 1999] to 300 years [Knight, 1975]. Riswan, Kentworthy and Kartawinata [1985] estimated recovery between 150-500 years).

We must also keep in mind that footprint effects are not evenly distributed. Moreover, we must keep in mind that the world-wide level of consumption is driven by the more advanced capitalist nations. In the US, for example, the ecological biocapacity is 4 hectares (9.9 acres) per person, meaning that there are 4 hectares of land available for consumption purposes per person. US consumption, however, is 7 hectares (17.3 acres) per person, meaning that the average American consumes 3 hectares (7.4 acres) of resources beyond the per-person ecological resources available in the US. Those resources are provided by other nations and that unequal exchange between US consumers and nature in foreign lands is facilitated by the capitalist world system. That is to say, overconsumption in one part of the capitalist world system (in one nation) is paid for by transferring ecological needs and withdrawals to nations that consume less, shifting consumption effects across nations (Stretesky and Lynch, 2009).

We can see this tendency toward ecological destruction and overconsumption in other measures as well. Global footprints indicate how much we consume, but not how much we destroy the environment by adding waste products (i.e., pollution) to nature. One indicator of these waste products is our carbon footprint or the quantity of carbon waste humans add to the environment. This waste is an indicator of the consumption of fossil fuel and chemical energy humans use, and can also be employed to understand related problems such as the production of entropy caused by humans (e.g., www.globalcarbonproject.org; http://co2now.org/Current-CO2/CO2-Now/global-carbon-emissions.html; www.epa.gov/climatechange/ ghgemissions/global.html). These data, like footprint data, indicate that we are consuming our way to extinction and taking the living earth along with us.

Despite the pretense that world governments are addressing this issue, environmentally, things are getting worse, not better. Even while nations endeavor to reduce their carbon footprints, the world level of carbon dioxide grows, and now is just short of the 400 ppm atmospheric carbon dioxide level (399.89). Many scientists suggest that the 400 ppm carbon dioxide level marks a tipping point in climate change, and that the negative impacts of the greenhouse effect will accelerate.

Pollution problems grow everywhere. Recent estimates suggest that pollution in China has grown so severe that it causes 1.2 million premature deaths annually (a figure well in excess – 89 times — of the number of homicide in China, which stand at about 13,400 annually). While those pollution related deaths are a small percentage of the Chinese population, the number of pollution related deaths are likely underestimated for a variety of reasons, such as classification of a death as pollution related. In addition, the effects of recent increases in pollution levels in China will not have an impact for up to another twenty years (representing an estimate of the time it may take for pollution exposure to cause death through disease processes), making the recovery from pollution a long term process in China, and indicating that the long term impact of the growth of pollution in China will be felt for decades. Other areas of the world where pollution is extensive, including several other Asian nations as well as the US, indicates that political leaders have not adequately dealt with the problem of pollution. Singapore, for instance, is currently wrapped in a thick smog blanket that is projected to last several weeks, where air pollution levels have reached a 16 year high. Some of that pollution is due to historically high levels of forest bur ns. To illustrate the extent of the problem, the air pollution index for Singapore reached 371 in June, 2013, whereas the previous high, 226, was set in 1997. In short, these observations indicate that the ecological and health consequences f ecological destruction are becoming more severe as humans continuously devour nature and change the very essence of the ecosystem that keeps them alive.

In the US, facilities that report to the US EPA estimated producing nearly 22.8 billion pounds of hazardous waste in 2011. While industries report releasing “only” 18% (4.1 billion pounds) of that waste directly into the environment and transferring the rest to hazardous waste handlers for disposal, research indicates that those reports likely under-estimate the volume of emissions by as much as 40% (de Marchi and Hamilton, 2006). Ignoring the possibility of under-reporting, we can estimate from those reports that US industries produced more than 220 billion pounds of waste in the past decade, and emitted more than 40 billion pounds of hazardous waste directly into the environment. Those hazardous emissions are accumulating to dangerous levels, increasing the probability that ecological damage of this type accelerates the likelihood of pollution related deaths and illnesses. Those emission estimates do not include emissions from “accidental chemical releases” or ACRs. In 2011, there were more than 30,000 reported ACRs in the US that released an uncounted volume of waste. Those incidents resulted in 1,270 deaths, and cost more than $15.8 million in damages by themselves.

In some places, new forms of environmental harms are emerging. In California, the “medical marijuana” industry has recently been discovered to be generating extensive ecological damage cause by marijuana farming. In addition to transforming forests into medical marijuana farms, marijuana growers are using rodenticides to protect their crops from wood rats. In recent months, the deaths of seven Pacific Fishers, a candidate for listing under the Endangered Species Act, have been linked to the use of those poisons. Only two populations of Pacific Fishers are believed to exist in the state of California — a state where the Pacific Fisher once was widespread. Marijuana farms in California have been established on hilltops, using methods similar to mountaintop removal mining. The hilltops are bulldozed clear of forest, shrubs and rock, creating impediments to streams, and impacting waterways used by salmon (Coho, Chinook and Steelhead) when the overburden is pushed down the hillsides. The bulldozed earth has also created erosion and landslide problems. Water dams and other water diversion methods used to irrigate the marihuana farms are also contributing to serious environmental problems. In other parts of California, the use of pesticides and new farming methods have caused a dramatic decline in what used to be one of the state’s most numerous bird species – the tri-colored black-bird. Data from the Audubon Society’s annual bird count in California indicates a 35% decline in tri-colored black-birds since 2008. The environmental problems for California don’t stop here, as recent studies suggest that California is losing its Central Valley underground aquifer, which feeds significant agricultural production. Shrinking underground aquifers, however, have become a common problem across the US.

Recent studies on the prevalence of autism among US children found that autism rates are higher in heavily polluted areas, providing an indication of a suspected link between autism and certain environmental pollutants (e.g., http://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/ newsarticle.aspx?articleid=1558422) . Across the world, studies indicate that the intensified use of pesticides is increasing the loss of species biodiversity, especially in Australia and in European nations (Beketov et al., 2013). In Turkey, an economic boom is leading to a loss of marine species diversity. Also in Australia, lead emissions from the mining industry are causing an increase in lead poisoning cases among children (McKay et al., 2013). In Virginia, the Hellbender Salamander is dying off, apparently from exposure to pollution. In Florida’s Indian River, 111 manatees, 46 dolphins and more than 300 pelicans have shown up dead in recent months, the possible victims of pollution exposure.

These are serious environmental problems, problems criminology seems largely incapable of recognizing as green crimes, forms of green victimization and as issues relevant to discussions of green injustice. The structure of criminology as a discipline has made it an antiquated discipline incapable of conceptualizing green crime and victimizations as serious issues, or to perceive the need for green theories of justice in the contemporary era. Criminology, which remains anchored to its ancient past, now stands as a discipline that has perverted the concept of crime and disfigured the meaning of justice. Within criminology, concepts such as “crime” and “justice” have relevance only within the limited space law provides for such idea. Criminology’s adoption of the legal definition of crime and justice has, for example, made these concepts into reflections of legalized jargon absent of any definitional clarity outside of the scope of law and its ability to institutionalize definitions of crime that it can precisely codify – that is, theoretically. The law does not speak to the general concept of crime, nor does it appreciate nor understand the concept of green crime and justice, or that as an institution, that law itself is merely a mechanism for reinforcing preexisting and unequal economic arrangements and the destructive tendencies of economic forms from which green crimes emerge.

In the era of ecological demise in which we are now embedded there is a need to reconstruct criminology so that it becomes relevant to addressing green crime and justice and the forms of ecological destruction the world capitalist system imposes. A criminology capable of less than this has become irrelevant to the widespread forms of green victimization and injustice that plagues the living system of earth (Gaia, as scientists call it) and the living species that depend on Gaia’s ability to reproduce the conditions for life for itself and other living species.

References

Beketov, Mikhail A., Ben J. Kefford, Ralf B. Schäfer, and Matthias Liess. (2013). “Pesticides reduce regional biodiversity of stream invertebrates.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences June 17.

Burkett, Paul. (2006). Marxism and Ecological Economics: Toward a Red and Green Political Economy. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Chadwick, Edwin. (1842). Report on the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain. London: W. Clowes & Sons.

De Marchi, S. and Hamilton, J. (2006), ‘Assessing the Accuracy of Self-reported Data: An Evaluation of the Toxics Release Inventory’, Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 32(1): 57–76.

Dunning, John H. (2003 ). The Moral Imperative of Global Capitalism: An Overview. Pp. 11-40 in J. H. Dunning (ed), Making Globalization Good: The Moral Challenges of Global Capitalism. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Engels, Fredrick. (1845[1973]). The Condition of the Working Class in England, 1844. Moscow:Progress Publishers.

Foster, John Bellamy. (2000). Marx’s Ecology: Materialism and Nature. NY: New York University Press.

Kovel, J. (2007), The Enemy of Nature: The End of Capitalism or the End of the World? New York: Zed Books.

Knight, D.H. (1975). A phytosociological analysis of species-rich tropical forest on Barro Colorado Island, Panama. Ecological Monographs 45: 259–284.

Lovelock, J. (2007), The Revenge of Gaia: Earth’s Climate Crisis & the Fate of Humanity. New York: Basic Books.

Lovelock, J. (2000), Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth. New York: Oxford Paperbacks.

Mackay, A. K., M. P. Taylor, N. C. Munksgaard, Karen A. Hudson-Edwards, and L. Burn-Nunes. (2013). “Identification of environmental lead sources and pathways in a mining and smelting town: Mount Isa, Australia.” Environmental Pollution http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2013.05.007

Mueller, Andreas D., Gerald A. Islebe, Flavio S. Anselmetti, Daniel Ariztegui, Mark Brenner, David A.Hodell, Irka Hajdas, Yvonne

Hamann, Gerald H. Haug, and Douglas J. Kennett. (2010). “Recovery of the forest ecosystem in the tropical lowlands of northern Guatemala after disintegration of Classic Maya polities.” Geology 38, 6: 523-526.

Riswan, S., J.B. Kentworthy and K. Kartawinata. (1985) The estimation of temporal processes in tropical rain forest: A study of primary mixed dipterocarp forest in Indonesia. Journal of Tropical Ecology1: 171–182.

Thackrah, Charles Turner. (1831). The Effects of the Principle Arts, Trades and Professions, and the Civic States and Habits of Living on Health and Longevity. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown & Green.

White, L.J.T. and J.F. Oates. (1999). New data on the history of the plateau forest of Okomu, southern Nigeria: An insight into how human disturbance has shaped the African rain forest. Global Ecology and Biogeography 8: 355–361.

Herman and Julia Schwendinger Publish New Book — BIG BROTHER IS LOOKING AT YOU, KID! IS HOMELAND FASCISM POSSIBLE.

Herman and Julia Schwendinger have published a new book, BIG BROTHER IS LOOKING AT YOU, KID! IS HOMELAND FASCISM POSSIBLE which thay are making available free of charge.

The book is a political treatise but it may be interesting academically

because of its analytic constructs. It employs their “Janus model” of

governance and a category entitled “customary repression,” referring to the

normalized century-old repression of left-wing ideas and policies. It

chronicles the qualitative changes in customary repression from the 1970s

and employs “parallels” (with the rise of fascism in Germany, Italy, Chile,

etc.) to realistically evaluate neofascist developments in the USA. It

points out that “bullshit” is the modus operandi of archconservatives

reviving McCarthyism in American universities. It describes, among other

things, the astonishing expansion of surveillance technology, the “Miami

model” of police brutality, the rise of Occupy Wall Street, and Obama’s

complicity in war crimes.

Big Bro can be downloaded (at no cost) from:

http://homelandfascism101.com/FreeEbook.htm

New Incinerator Rule Implementation Postponed By EPA: Obama’s New Conservative Environmental Approach.

New Incinerator Rule Implementation Postponed By EPA: Obama’s New Conservative Environmental Approach

Michael J. Lynch

Department of Criminolgoy and

School of Global Sustainability

University of South Florida

The G.W. Bush Administration is widely regarded as having established the worst environmental record of any Administration since the founding of the EPA during Nixon’s presidency. The election of Obama brought great hopes for a redirection in environmental policies in the US. In some ways, the Obama Administration has delivered on those hopes revising, for example, the outdated and fairly stagnant fuel economy standards.

Since the midterm election cycle in which Republicans gained a large number of seats in the US House of Representatives, however, environmental guidance from the White House has weakened. On May 16th, for example, the EPA postponed instituting a rule that would have strengthened air pollution standards incineration at major industrial facilities. This postponement follows a series of deferred rulings involving coal ash management, mountain top removal mining and a proposed reconsideration of stricter regulations imposed on cement manufacturing facilities. In addition, just last week, the Obama Administration announced plans to expand oil exploration and natural gas drilling on previously excluded lands.

Background

Action on industrial on site incineration regulations had been delayed throughout the Bush Administration. On February 21, 2011, the EPA issued its final ruling on this issue. That ruling was induced by court review by the District Court of Washington D.C.. The February ruling sought to reduce emissions of air pollutants at on-site incinerators referred to as existing and new Boilers, Commercial and Industrial Solid Waste Incinerators (CISWI), and Sewage Sludge Incinerators (SSI). These provisions relate to sections 112 and 129 of the Clean Air Act.

As the EPA notice of final ruling notes (EPA FINAL RULING) the final rule is designed to reduce harmful air pollution emissions by industrial facilities including fine particle, ozone, mercury, hazardous air pollutants (HAPS), and dioxin. The EPA estimates that the health benefits to the American public amount to between $22-$54 billion annual (beginning in 2014).

The final rules apply to a variety of incinerators. As noted in the final rule statement by EPA, the rules affect 13,800 boilers at large facilities, 187,000 small source boilers, 88 commercial and municipal incinerators, and 200 sludge incinerators. In total, the rule is estimated to affect 201,088 incinerators.

In describing the benefits of the rule, the EPA noted that decreasing pollution from these sources will: (1) directly benefits communities near these facilities; (2) reduce the occurrence of health effects associated with these pollutants including heart disease, developmental disabilities, cancer and premature death; (3) specifically, the rule is estimate to prevent 2,600 premature deaths annually, 4,100 heart attacks, and 42,000 asthma attacks annually; and (4) produce $10-$24 in health benefits for every dollar spent on meeting the standard.

As evident in the rule making notice, the health care outcomes associated with reducing these forms of pollution are significant. In financial terms alone, the savings are significant. The EPA estimates that meeting the rule will require an investment of $1.9 billion. Spread out across the more than 200,000 affected facilities, the cost average appears insignificant — $10,000 per facility. To be sure, there are variations in costs across small and large polluters, but the per facility cost is hardly large.

As noted, EPA estimates that health costs savings are between $10-$24 dollars for each dollar spent on achieving compliance with the rule. The EPA states that annual savings from compliance are between $22-54 billion. Since achieving compliance costs are minimal and health care costs are long term, the economic benefit of this rule making change is highly understated.

Empirical Evidence: The Effect of Environmental Rules on the Economy and Jobs

The Obama Administration’s new environmental policies seem to be driven by criticisms from conservatives and business leaders that enhanced environmental regulations will slow business growth and lead to further job loses. Given the shape of the economy, the Administration has chosen to sacrifice improving the health of Americans through enhanced environmental regulation to political rhetoric on the effects of environmental regulations on job markets and the economy.

Empirical studies of the effect of environmental regulations have not focused much attention on job market conditions, but rather have examined the broader claim that environmental regulations impact the location and expansion of industry. In a 1996 study in the Journal of Public Economics, (“Environmental Regulations and Manufacturers’ Location Choices”), Arik Levinson found that variation in environmental regulations did not affect industrial location. In an article in the Journal of Regional Sciences (“Effects of Environmental Regulations on State-Level Manufacturing Capital Formation,” 2006), the authors found that environmental regulations had small effects on net capital formation, and that these results varied by region and state. These results are confirmed by an earlier (1988) study by Bartik in Growth and Change: A Journal of Urban and Regional Planning. Specifically, Bartik examined the effect of state environmental regulations on the location of Fortune 500 corporations, and found no relationship.

In an article directly addressing the employment-environmental regulation effect debate, Berman and Bui’s 2001 analysis of air pollution regulation on employment in the Los Angeles area (Journal of Public Economics) found only small effects for air pollution regulations on employment. Moreover, these effects were found to be related to the capital intensive nature of affected industries where employment has already been reduced through mechanization. In addition, the authors discovered that the affects of new air pollution regulations had a large impact on air pollution and air quality. One can conclude from this study that these two effects – the large effect on air quality and the small effect on employment — need to be considered side by side and weight appropriately against one another since a larger portion of the population is impacted and protected by increased pollution regulations than is negatively affected.

In a more recent study, the first to examine the environmental regulation-employment effect outside the US, Cole and Elliot found no effect of environmental regulations on employment in the UK (“Do Environmental Regulations Cost Jobs? An Industry Level Analysis of the UK,” 2007, The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy). This study’s findings, while not from the US, indicate that protecting the environment and employment are not necessarily competing interests.

While the analysis referred to above report non-significant or small effects, there are studies, largely from privately funded research groups but which also include some academic work, which find that enhanced environmental regulations do impact job loss. As more recent research suggests, however, the results of many of those studies are limited by their use of cross-sectional rather than panel data. Panel data, by their very nature, control for some of the effects that occur over time, though their ability to do so may also depend on the length of the series.

One of the issues that has not been addressed in prior studies is cotemporaneous employment gains in industries that provide equipment and technology related to pollution control. For example, it is likely that the small losses in employment attributed to environmental regulation in some studies may be entirely offset by employment gains in pollution control industries that provide technology required by extended, enhanced or new environmental regulations. This issue has not been directly addressed in empirical studies on pollution regulation in the US, though this argument is recognized in more general terms in the environmental literature.

One study in Europe published as a working paper by the Centre for European Economic Research (ZEW Discussion Paper No. 01-08; “The Employment Impact of Cleaner Production on the Firm Level Empirical Evidence from a Survey in Five European Countries,” 2001, by Rennings and Zwick) examined the issue of job lose and creation related to environmental regulations. The data employed in that study were collected from 1500 European firms. The researchers found that environmental regulations that produce service innovations in response to environmental regulations create jobs in small firms. In contrast they found that regulations requiring technological innovation had no net effect on employment. The researchers also noted that cleaner technology regulation enhanced employment compared to end-of-pipe regulations.

Ironically, the researchers also discovered that firms that experienced cost reductions as a result of adapting to new environmental regulation by employing environmental innovation saw a decline in employment. One can concluded form these results that environmental regulations may reduce employment due to the positive effects of environmental regulations for firms. In other words, while job loses may occur, they result from labor saving environmentally related innovations that saved firms money and consequently increase profitability.

Conclusion: Obama, Public Health, Environmental Protection and Jobs

In contrast to the position of industry on the association between expenditures on meeting environmental rules that protect public health and jobs, and considering the large health impact of CISWI and SSI rules on public health and their economic benefits, an alternative interpretation can be offered. First, dead people don’t need jobs. In their efforts to undermine rule making that preserves public health, those who have an economic interest in weakening these standards are valuing a small investment over the lives of the American public – and noted in the EPA report, 4,200 lives each and every year these rules are not met. Moreover, given that the new rules are not as stringent as they might be to protect public health, the estimate of 4,200 saved lives could be higher if the proposed rules were stronger and protected the public better.

Second, the interests that favor undermining the proposed rule clearly over-estimate the effect of pollution laws that protect public health on the economy and on job loss. If, as estimated here, the average investment across the more than 200,000 facilities affected by this rule is a mere $10,000, this should not lead to significant job loses. Moreover, those loses would need to be balanced against the 4,200 lives saved annually and the economic health related benefits to the average American which are 10-24 times higher than the investment cost and last, in effect, forever as opposed to the one time expenditures required by facilities to meet these new standards.

The economic problems in the US economy have been a long time in the making and are not the result of environmental regulations that protect the general public. Moreover, what is not considered by opponents of these rules are the costs savings for them in terms of declining health care premiums that would result from cleaning up the environment.

There is little reason to oppose environmental safety rules except as these are related to business profit. It is a crass society and a crass presidential administration that prefers profits to people’s lives and the health of the American public.

Criminal Justice Education Moves Online

Is that an Elephant in the Living Room?

Kenneth W. Mentor

University of North Carolina Wilmington

The popularity of criminal justice as a major, combined with the potential to reach justice professionals with distance technology, has resulted in the creation of many online degree programs. However, scholarly organizations in criminal justice barely acknowledge online learning. ACJS Certification Standards do not allow certification for most non-traditional programs. The failure to respond to rapid changes may be preventing our discipline from achieving goals related to criminal justice education.

The popularity of criminal justice education, combined with the potential for reaching many justice professional with distance technology, makes criminal justice an attractive candidate for online course and degree delivery. In fact, the discipline of criminal justice has been seen as fertile ground for new students and growth in certain segments of the market for criminal justice education has been very impressive.

Allen and Seaman (2008) report that over 3.9 million higher education students were taking at least one online course during the fall 2007 term, a 12.9% increase over the previous year. In contrast, there was just a 1.2% growth of the overall higher education student population. Over 20% of all U.S. higher education students were taking at least one online course in the fall of 2007, accounting for nearly 22% of total enrollment (Allen and Seaman, 2008). While the rate of growth varies from year-to-year, there is no indication that growth rates are leveling. Economic conditions, coupled with a growing emphasis on sustainability, are likely to accelerate the expansion of online learning, even if traditional enrollments decline.

While non-profit institutions are discovering this market, they are relatively late to the game. For-profit institutions currently comprise a significant percentage of the online learning market and are expected to continue to capture a large share of the market. The growth of some of these proprietary institutions has been remarkable. For example, Kaplan University has grown from 34 online students in 2001 to more than 48,000 online and on-ground students in 2008 (Kaplan, 2009). Kaplan first began offering criminal justice degrees in 2003. Since then, enrollment in the School of Criminal Justice has grown to over 7,000 students and more than 14 criminal justice degree or certificate programs (DiMarino, 2008).

Although we will see an increased emphasis on traditional students as the learning benefits of online learning are more widely acknowledged, those currently interested in online education are attracted by convenience, availability, and scheduling flexibility. This is especially true for criminal justice professionals closely connected to the communities in which they work. Online learning allows these professionals to return to college, or complete non-degree training experiences, without leaving their jobs and communities.

Given this rapid growth, accompanied by many online options in our discipline, it would seem logical to find criminal justice and criminology educators at the forefront of the distance learning movement. However, scholarly organizations in criminal justice and criminology barely acknowledge the rapid advancement of online learning. The ACJS Certification Standards for Academic Programs focus on campus-based programs and do not appear to acknowledge the possibility of certification for non-traditional programs that are not connected to, and administered by, faculty teaching in a traditional campus-based program (ACJS, 2005). While the “Teaching Tips” column in The Criminologist has been an exception, with several articles of interest to online educators, the ASC has been similarly silent on the issue of online education.

Rapid change in online learning has increased the importance of effective accreditation review, in many cases leading committed faculty to treat accreditation as an important opportunity rather than a necessary evil. Educators are becoming increasingly familiar with the expectations of regional accrediting bodies, acknowledging that accreditation standards represent important measures that can inform our efforts to focus on the development of effective learning outcomes.

As we begin to rely more heavily on distance learning models we can expect an increased emphasis on accreditation. Entirely new institutions are being formed to provide educational opportunities. Rather than force a hierarchy that places “traditional” models in a superior position, it is important to acknowledge the potential benefits of these rapid changes. Many discussions of online education rely on broad generalizations about quality, student motivations, and the entrepreneurial focus now being seen in higher education. We also see inaccurate assumptions regarding the quality of traditional models. Many changes will be necessary as we continue our efforts to build high quality learning environments.

Dedicated educators can certainly work to assure quality online educational experiences without the support of discipline-specific scholarly organizations. We can start by questioning the effectiveness of online learning environments. Quality varies widely, creating a void that could be filled with discipline specific guidelines. Educators may also want to examine the process through which courses and programs are created. For example, are criminal justice faculty involved with developing online courses, or has the process been turned over to course developers with very little discipline-specific knowledge?

Another issue is whether faculty members with terminal degrees are teaching courses and exercising responsibility for overall program quality. We also see an emphasis on very different instructor qualifications as proprietary institutions give hiring preference to instructors with “real world” experience. Arguably, the courses we teach, and students we serve, are changing as a result of events that many in our disciplines have yet to acknowledge.

We are also experiencing a variety of new learning models, including accelerated options, certificates, and other innovations. New subsections of our discipline are being created as online criminal justice degree programs, presently dominated by proprietary institutions, respond quickly to market demands. Entrepreneurial institutions have responded to these demands by developing courses, degrees, concentrations, and certificates in areas such as forensics, cyber-crime, homeland security, business continuity, and emergency management. In short, the teaching of criminology and criminal justice are changing as a result of marketing decisions.

How can online learning be better? We are just beginning to explore this terrain. While many changes will be needed, often relying on new learning tools, there is no doubt that learning is being permanently transformed. If we are truly experiencing a paradigm shift, this shift is constrained by our reluctance to acknowledge this change. The higher education paradigm, honed and perfected over time, has served us well. Unfortunately, this model may now be preventing us from moving toward higher quality learning environments.

The world of higher education is clearly changing. New technology has created many new learning opportunities and we are just beginning to experience the benefits. This is occurring during a time in which we are also seeing new demands from students. While we can question the absence of the scholarly organization to which many of us belong, these changes have lead to many new opportunities for educators.

References

DiMarino, F. (2008). Viewpoint interview with Frank DiMarino, The Washington Post. Available at: http://discuss.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/zforum/05/kaplan_viewpoint2.htm

Kaplan (2009). Kaplan Higher Education Fact Sheet. Kaplan University. Available at: http://talent.kaplan.edu/Assets/PDF/kaplanhistory.pdf

The November Coalition

The November Coalition

Kenneth Mentor

University of North Carolina Wilmington

In 1970, 16.3% of the Federal Prison population was serving time because of drug offenses. This represented a total of 3,384 individuals. By 2000, Prisoners sentenced for drug offenses represented a total of 57%. On September 30, 2000, the date of the latest available data in the Federal Justice Statistics Program, Federal prisons held 73,389 sentenced drug offenders. State prisons also hold a large number of drug offenders. In 2000, drug law violators comprised 21% of all adults serving time in State prisons. This represents 251,100 out of 1,206,400 State prison inmates. In 2001, 1 in every 146 U.S. residents was incarcerated in State or Federal prison or a local jail. As a result, the U.S. nonviolent prisoner population is larger than the combined populations of Wyoming and Alaska. As we know, the corrections population is not limited to those in prison. There were 5.9 million adults in the ‘correctional population’ by the end of 1998. This means that 2.9% of the U.S. adult population — 1 in every 34 — was incarcerated, on probation or on parole. The vast majority of those incarcerated for nonviolent offenses is behind bars, or otherwise involved with the corrections system, for a drug related offense.

If incarceration rates do not change, 1 of every 20 Americans (5%) can be expected to serve time in prison during their lifetime. For African-American men, the number is greater than 1 in 4 (28.5%). The primary reason for the remarkable increase in the incarceration rate is the adoption of mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenders. Since the enactment of mandatory minimum sentencing the Federal Bureau of Prisons budget has increased by 1,954%. Its budget has jumped from $220 million in 1986 to $4.3 billion in 2001. The November Coalition formed in response to the massive incarceration of offenders. In addition to the systemic problem of over-incarceration the November Coalition also points out the disproportionately devastating impact of mandatory sentencing on individuals and families.

According to their web site, the November Coalition includes “a growing body of citizens whose lives have been gravely affected by our government’s present drug policy. We are prisoners, parents of those incarcerated, wives, sisters, brothers, children, aunts, uncles and cousins. Some of us are loving friends and concerned citizens, each of us alarmed that drug war casualties are rising in absolutely horrific proportions.” The November Coalition is a non-profit, grassroots organization with the goal of “educating the public about the destructive increase in prison population in the United States due to our current drug laws. We alert our fellow citizens, particularly those who are complacent or naive, about the present and impending dangers of an overly powerful federal authority acting far beyond its constitutional constraints. The drug war is an assault and steady erosion of our civil rights and freedoms by federal and state governments.”

Formed in 1997 by survivors and victims of the drug war, the November Coalition uses real life examples to illustrate how a drug arrest can become a “frightening introduction to conspiracy statutes, government’s liberal use of informants, guideline-sentencing laws, and the nightmare usually leaves defendant and family confused and full of despair.” Long-term imprisonment has dramatic effects on personality and personal relationships. Prisoners suffer from severe restrictions on their human and constitutional rights, and all of these difficulties exact a toll on both the prisoner and those who love them.

Stories told by the Coalition provide support for the belief that tax dollars are endlessly poured into an ever expanding prison industrial complex that exists, in part to incarcerate the poor. The Coaltion argues that the discriminatory impact of drug policies should have been predicated, and if not, the discriminatory impacts are certainly clear to today’s policymakers. In effect, the policies create a situation in which the most vulnerable are least able to defend against injustice. In effect, our policies do not represent a realistic a war on drugs. They represent a war on people. The Coalition points out the similarities between alcohol prohibition of the 1920’s and drug prohibition today. Drug users have been dehumanized through demonizing propaganda, in particular “the crack epidemic,” that dominated national media during the late 1980’s.

The November Coalition seeks to rehumanize the victims of the drug war by telling their stories. By reading these stories it is clear that many drug war victims are regular people, good citizens and neighbors, whose lives have been derailed by a misguided war on drugs. The Coalition publishes “The Razor Wire” to report on drug policy reform efforts, legislative updates, and news about drug law vigils and meetings. This publication also includes letters from prisoners and others who have been victimized by the war on drugs. The organization also uses its extensive website, including “The Wall,” an online collection of prisoner photos and stories, to document the impact of the war on drugs.

The November Coalition provides an example of the internet’s potential for grassroots challenges to policy. The organization was started by a handful of people with a strong desire to educate people about a policy that they believed was having a devastating impact on individuals and society. As the November Coalition has demonstrated, the internet can be an extremely effective tool for information sharing. The organization has also demonstrated the internet’s potential as a tool for organizing those who share an opposition to a policy that has shaped our justice system, filled our prisons, and shaped the societies of America and many other countries.

References and Suggested Reading

Bonczar, T. and Glaze, L. (1999). “Probation and Parole in the United States.” Bureau of Justice Statistics. Washington DC: US Department of Justice.

Harrison, Paige M. and Beck, A.J. (2002). “Prisoners in 2001,” Bureau of Justice Statistics. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice.

Irwin, J., Schiraldi, V. and Ziedenberg, J. (1999). America’s One Million Nonviolent Prisoners. Washington, DC: Justice Policy Institute.

Websites

November Coalition – http://www.november.org

Common Sense for Drug Policy – http://www.csdp.org/

Criminal Justice Policy Foundation – http://www.cjpf.org/

Drug Policy Alliance – http://www.drugpolicy.org/

Media Awareness Project – http://www.mapinc.org/

National Drug Strategy Network – http://www.ndsn.org/

Students for Sensible Drug Policy – http://www.ssdp.org/

Literacy in Corrections

Literacy in Corrections

Kenneth Mentor and Molly Wilkinson

Millions of individuals are housed in correctional facilities. Literacy skills are important to these individuals and can aid in the successful functioning of the institutions. Many prison jobs require literacy skills and inmates are often required to fill out forms to make requests. Reading and writing provide productive options for passing time while in prison. Letters to family and friends are a vital link to the outside world. Literacy skills are also important for those who will leave prison and attempt to reintegrate into the community. Jobs, continued education, and many social opportunities depend on the ability to read and write – regardless of whether an individual is in prison.

Research consistently demonstrates that quality education is one of the most effective forms of crime prevention. Educational skills help deter people from committing criminal acts. As a result, educational programs decrease the likelihood that people will return to crime, and prison. In the United States, a “get tough on crime” mentality has resulted in a push to incarcerate, punish, and limit the activities of prisoners. Over the last 10 years political pressure has led to the elimination of funding for many corrections education programs. Many programs that have been demonstrated as extraordinarily effective have been completely eliminated.

Literacy programs continue in many correctional facilities in spite of program cuts. These programs meet with little political resistance, in part because they can be run at a relatively low cost. In addition, state and federal guidelines that encourage the development of literacy skills typically apply to all citizens, including prisoners. Prison literacy programs also benefit from volunteer efforts of organizations and individuals.

Need for Literacy Programs

The total number of prisoners in federal or state facilities was almost 1.4 million in 2000. Nearly 600,000 inmates were released in 2000, either unconditionally or under conditions of parole. Many of those released will be rearrested and will return to incarceration. Costs of this cycle of incarceration and reincarceration are very high. Corrections education has the potential to greatly reduce these costs. One study indicates that those who benefited from correctional education recidivated 29% less often that those who did not have educational opportunities while in the correctional institution (Steurer, Smith, and Tracy, 2001). When we consider the high cost of imprisonment, the increasing prison population, and the increasing number of individuals released from prison at the end of their sentences, literacy programs provide a cost effective opportunity to reduce crime and the costs of crime.

Illiteracy is perhaps the greatest common denominator in correctional facilities. Data collected from the National Adult Literacy Survey (NALS) show that literacy levels among inmates is considerably lower than for the general population. For example, of the 5 levels measured by the NALS, 70% of inmates scored at the lowest two levels of literacy (below 4th grade). Other research suggests that 75% of inmates are illiterate (at the 12th grade level) and 19% are completely illiterate. Forty percent are functionally illiterate. In real world terms, this means that the individual would be unable to write a letter explaining a billing error. In comparison, the national illiteracy rate for adult Americans stands at 4%, with 21% functionally illiterate.

A related concern is that prisoners have a higher proportion of learning disabilities than the general population. Estimates of learning disability are as high as 75-90% for juvenile offenders. Low literacy levels and high rates of learning disabilities have contributed to high dropout rates. Nationwide, over 70% of all people entering state correctional facilities have not completed high school, with 46% having had some high school education and 16.4% having had no high school education at all. Since there is a strong link between low levels of education and high rates of criminal activity, it is logical to assume that high dropout rates will lead to higher crime rates.

Prison Literacy Programs

The correctional facility provides a controlled education setting for prisoners, many of whom are motivated students. However, the prison literacy educator faces many challenges. Students in these programs evidence a wide range of potential and have had varying educational experiences. The educator’s challenge is compounded by the uniqueness of prison culture and the need for security. Prisons adhere to strict routines, which may not be ideal in an educational setting. Inmates are often moved from one facility to another. This movement interrupts, or ends, the individual’s educational programming. These structural issues are accompanied by social factors that can further limit learning opportunities. Peer pressure may discourage attendance or achievement. Prison administrators have varying degrees of support for education – especially if they see education as a threat to the primary functions of security and control.

In spite of the challenges, examples in the literature demonstrate that programs based on current thinking about literacy and sound adult education practices can be effective in prison settings. Successful prison literacy programs are learner centered, recognizing different learning styles, cultural backgrounds, and multiple literacies (Newman et al. 1993). Successful programs typically use learner strengths to help them shape their own learning. Historically, literacy education has been offered to the general population by two volunteer agencies: Literacy Volunteers of America (LVA) and Laubach Literacy International. Both have a presence in correctional facilities through trained volunteers and staff. However, because educational programming depends on the philosophy and policies of the correctional facility, there is little data to suggest uniformity in delivery of literacy services to inmates.

Testing and curricula are two common elements in many prison literacy programs. Several standardized reading tests are available to literacy instructors. Besides the Test of Adults in Basic Education (TABE), two other tests are commonly used. One, the Grey Oral Reading Test, measures the fluency and comprehension of the learner. For example, it determines the learner’s ability to recognize common written words such as “car,” “be,” “house,” “do” by sight or in context. A second commonly used test for literacy skills is the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL). This test is divided into five levels ranging from assessing the learner’s ability to fill out a deposit slip (Level I), determining the difference in price between two items (Level II) to demonstrating proficiency in interpreting complex written passages (Level V). These tests can be used to assess needs, track progress, and demonstrate success to the learner and to administrators who may be called on to support the program.

Several literacy curricula are available to prison educators. The National Institute for Literacy developed standards for literacy as a component of lifelong learning. This program focuses on skill acquisition in three areas: worker, family member, and citizen. The standards are broken down into four general areas with several sub-areas. For example, “communication” is broken into the following sub-areas: 1) reading with understanding; 2) conveying ideas in writing; 3) speaking so others can understand; 4) listening actively; and 5) observing critically. The curriculum utilizes activities that are relevant to the learner’s life to develop skills in reading. Laubach Literacy offers curricula that can be used in classroom settings or in one-on-one instruction. “Reading Is Fundamental” and “Project Read” are examples of federally funded literacy programs that offer text-based curriculum.

Although there are similarities in each of these programs, data does not suggest a standardized delivery method for literacy programs in correctional facilities. The programs generally include reading, writing, calculating, listening, speaking, and problem-solving as core parts of a literacy curriculum. In general, successful programs are learner centered, participatory, sensitive to the prison culture, and linked to post-release services.

Conclusion

Since the 70s, the correctional philosophy has shifted from a rehabilitative to a punitive approach. As a result, today’s correctional facilities are viewed primarily as a means of separating criminals from the public. Although prisons have become increasingly punitive, correctional facilities remain responsible for addressing literacy problems among the corrections population. The logic behind providing literacy services in prison is that all of society benefits by allowing access to educational resources that are available to everyone else. As such, literacy programs should not be seen as “special treatment” for prisoners. The federal government encourages literacy skill improvement in all entities, including prisons, that receive federal aid and at least 26 states have enacted mandatory educational requirements for certain populations. These policies demonstrate the importance placed on efforts to improve literacy skills.

Although there are challenges, literacy programs can provide relatively inexpensive educational program within correctional institutions. When we consider the high cost of imprisonment, coupled with a growing prison population, literacy programs provide a cost effective opportunity to improve the job related skills of incarcerated individuals. A large percentage of these individuals will be released from prison and will be expected to successfully, and lawfully, reintegrate in our communities. Literacy education provides a large payoff to the community in terms of crime reduction and employment opportunities for ex-offenders. Investments in these programs have been confirmed as wise, and cost effective, public policy.

References and Suggested Reading

American Corrections Association (2002). http://www.aca.org

Bureau of Justice Statistics (2002). “Key crime and justice facts at a glance.” http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/glance.htm

Haigler, K. O.; Harlow, C.; O’Connor, P.; and Campbell, A. (1994). Literacy Behind Prison Walls. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Kerka, S. (1995). “Prison Literacy Programs.” Eric Digest no. 159. Columbus, OH:

Kollhoff, M. (2002). “Reflections of a Kansas Corrections Educator.” The Journal of Correctional Education, 53(2), June 2002, 44-45.

Laubach Literacy Oranization (2002). http://www.laubach.org

Leone, P.E. and Meisel, S. (1997). “Improving educational services for students in detention and confinement facilities.” Childrens’ Legal Rights Journal, 17(1), 2-12.

LoBuglio, S. (2001). “Time to reframe politics and practices in correctional education.” In J. Comings, B. garner and C. Smith (Eds.), Annual Review of Adult Learning and Literacy, Vol.2. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

National Adult Literacy and Learning Disabilities Center (1996). “Correctional education: A worthwhile investment.” Linkages: Linking Literacy and Learning Disabilities. Washington, DC: The National Institute for Literacy, 3(2), Fall 1996.

National Institute for Literacy (1999). “Equipped for the future standards.” http://www.nifl.gov/lincs/collections/eff/eff.html

Newman, A. P.; Lewis, W.; and Beverstock, C. (1993). Prison Literacy. Philadelphia, PA: National Center on Adult Literacy.

Paul, M. (1991). When Words are Behind Bars. Kitchener, Ontario: Core Literacy.

Project READ. (1978). “To make a difference.” In M.S. Brunner (Ed.1993), Reduce recidivism and increased employment opportunity through research-based reading instruction (pp. 20-27). Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Quinn, M.M. Rutherford, R.B., Leone, P.E. (2001). “Students with disabilities in correctional facilities.” ERIC Digest no. E621.

Rutherford, R.B., Nelson, C.M., and Wolford, B.I. (1985). “Special education in the most restrictive environment: Correctional Special Education.” Journal of Special Education, 19, 59-71.

Steurer, S., Smith, L., Tracy, A. (2001). “Three State Recidivism Study”. Prepared for the Office of Correctional Education, US Department of Education. Lanham, MD: Correctional Education Association.

Tolbert, M. (2002). “State Correctional Education Programs.” Washington, D.C.: National Institute for Literacy. http://www.nifl.gov/nifl/policy/st_correction_02.pdf

GED and Corrections

The GED and Corrections

Kenneth W. Mentor

University of North Carolina Wilmington

The General Educational Development (GED) Exam assesses skills and general knowledge that are acquired through a four-year high school education. The exam changes periodically, most recently in January 2002, in an effort to keep up with knowledge and skills needed in our society. The exam covers math, science, social studies, reading, and writing. All of the test items are multiple choice except for a section in the writing exam that requires GED candidates to write an essay. The complete exam takes just under eight hours to complete and is typically broken down into several sections that can be taken over time.

Research that assesses the value of the GED examines employment and the likelihood of continuing with formal education after earning the GED. Scholars have also examined whether the GED is equivalent to a high school diploma. Past research indicates that employees with a GED are not the labor market equivalents of regular high school graduates. Those who leave school with very low skills benefit from obtaining a GED. However, this advantage is lessened for those who have obtained other employment-related skills. The message gained from much of the research is that it is best to remain in school. While the GED has value, it should not be seen as a replacement for four years of high school.

The GED and Corrections

There has been little research examining the impact of obtaining a GED in corrections settings. The majority of studies indicate that earning GED while in prison reduces the likelihood of returning to prison. However, some researchers have criticized the methodology used in studies that focus on recidivism since it may be argued that those who choose, or are chosen, for corrections education programs benefit most from the experience since they have already indicated a willingness to “stay out of trouble.” Arguably, these are the people who will benefit most from any efforts to increase their chances of success. It may be difficult to blame corrections education programs that focus on those most likely to benefit from the program.

Another problem regarding an effort to demonstrate the value of a prison GED, in comparison to a high school diploma or GED earned in a traditional setting, is related to the complexity of factors that surround an individual in the labor market. It is possible that the impact of earning a GED in prison is not great enough to overcome the negative effect incarceration can have on employment opportunities. Employers may be reluctant to hire someone who has served time in prison. In fact, a felony conviction can disqualify an individual for employment in some professions. Given the barriers placed before individuals who seek employment after prison, it may be difficult to demonstrate the impact of a single educational experience.

Although the employment related impacts of the GED earned corrections settings are difficult to assess, research has consistently demonstrated that corrections education can significantly reduce recidivism. A 1987 Bureau of Prisons report found that the more education an inmate received, the lower the rate of recidivism. Inmates who earned college degrees were the least likely to reenter prison. For inmates who had some high school, the rate of recidivism was 54.6 percent. For college graduates the rate dropped to 5.4 percent. Similarly, a Texas Department of Criminal Justice study found that while the state’s overall rate of recidivism was 60 percent, for holders of college associate degrees it was 13.7 percent. The recidivism rate for those with Bachelor’s degrees was 5.6 percent. The rate for those with Master’s degrees was 0 percent. The Changing Minds study, which focused on the benefits of college courses in a women’s prison, calculated that reductions in reincarceration would save approximately $900,000 per 100 student prisoners over a two-year period. If we project these savings to the 600,000 prison releases in a single year, the saving are enormous.

In addition to gains related to recidivism, prison-based education programs provide benefits related to the functioning of prisons. These programs provide incentives to inmates in a setting in which rewards are relatively limited. These classes also provide socialization opportunities with similarly motivated students and educators who serve as positive role models. Educational endeavors also keep students busy and provide intellectual stimulation in an environment that can be difficult to manage when prisoners break rules in search of an activity that breaks the monotony of prison life. Many prisons provide incentives for inmates who participate in corrections education. Opportunities to earn privileges within the facility, increased visitation, and the accumulation or loss of “good time” that can lead to earlier parole, are used to motivate the student while providing incentives for appropriate behavior within the facility.

Prison educators face many challenges. Inmates who choose to enroll in corrections-based courses are not necessarily any different from students who enroll in GED courses in other settings. The range of abilities can include very gifted students, students who face challenges, and students who have various motives for enrolling in the course. However, the educational setting is very different. Challenges faced by corrections educators are compounded by the uniqueness of prison culture and the need for security. Prisons adhere to strict routines that may not be ideal in an educational setting. In addition, inmates are often moved from one facility to another. This movement interrupts, or ends, the individual’s educational programming. These structural issues are accompanied by social factors that can further limit learning opportunities. The student may be very motivated to earn an education but he or she remains in an environment in which conflicting demands may limit the opportunity to act on that motivation. For example, other prisoners may not support the individual’s educational efforts.

Prison administrators may also have varying degrees of support for education – especially if they see education as a threat to the primary functions of security and control. GED courses may be seen as a burden to prison administrators who believe their primary goal is confinement. However, in many cases administrators are required to provide educational opportunities. At least 26 states have mandatory corrections education laws that mandate education for a certain amount of time or until a set level of achievement is reached. Enrollment in correctional education is also required in many states if the inmate is under a certain age, as specified by that state’s compulsory education law. The Federal Bureau of Prisons has also implemented a policy that requires inmates who do not have a high school diploma or a GED to participate in literacy programs for a minimum of 240 hours, or until they obtain their GED.

States typically provide corrections education funding based, in part, on success as measured by the rate of GED completion. In addition to state funding, the federal government provides support to state correctional education through the Adult Education and Family Literacy Act (AEFLA), which became law in 1998. However, funding often fails to keep pace with needs. Legislation over the past 20 years, a time in which the prison population has grown at unprecedented levels, has resulted in significant cuts in corrections education funding. This has resulted in the elimination of many programs. Ironically, the “get tough on crime” mentality resulted in the elimination of many programs that were effective in reducing crime.

Conclusion

Studies consistently indicate that an individual who benefits from education while in prison is less likely to return to prison than someone who has not had the benefits of education while in prison. There is some question as to why corrections-based education leads to lower recidivism. This is a complex process, and difficult to measure, but it appears that the ability to find and hold a job consistently functions to reduce the chance that an individual will commit crime. Individuals who increase their education also increase their opportunities. Individuals who take classes while in prison improve their chances of attaining and keeping employment after release. As a result, they are less likely to commit additional crimes that would lead to their return to prison.

The benefits of earning a GED while in prison are difficult to demonstrate. Individuals may find it difficult to obtain employment after serving time in prison. Potential employers may benefit from education regarding the realities of employing someone who has completed his or her punishment and is attempting to return to a productive life outside prison walls. It may also be time to question the belief that tougher prisons, with limited efforts to educate or otherwise rehabilitate offenders, reduce crime. The “get tough on crime” mentality has resulted in the elimination of many corrections education programs. Individuals in prison are typically burdened with many educational deficiencies. In many cases the lack of skills limited options, resulting in criminal acts. Upon release from prison, with limited education and job experience that is well below the level gained by those outside prison, it is no surprise that many individuals will head down the path that originally led them to prison.

FURTHER READING

Batiuk, M, Moke, P.and Rountree, P. (1997). “Crime and Rehabilitation: Correctional Education as an Agent of Change – A Research Note,” Justice Quarterly, 14(1).

Bureau of Justice Statistics (2002). “Key crime and justice facts at a glance.” http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/glance.htm

Fine, M., et.al. (2001) Changing Minds: The Impact of College in a Maximum Security Prison. The Graduate Center of the City University of New York. http://www.gc.cuny.edu/folio/index.htm.

Gerber, J. and Fritsch, E. (1993). Prison Education and Offender Behavior: A Review of the Scientific Literature. Huntsville, TX: Texas Department of Criminal Justice, Institutional Division.

Greenwood, P.W., Model, K.E., Rydell, C.P. and Chiesa, J. (1996). Diverting children from a life of crime: Measuring costs and benefits. Santa Monica, CA: Rand.

Haigler, K. O.; Harlow, C.; O’Connor, P.; and Campbell, A. (1994). Literacy Behind Prison Walls. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Harer, M. (1995). “Prison Education Program Participation and Recidivism: A Test of the Normalization Hypothesis,” Washington, DC: Federal Bureau of Prisons.

LoBuglio, S. (2001). “Time to reframe politics and practices in correctional education.” In J. Comings, B. garner and C. Smith (Eds.), Annual Review of Adult Learning and Literacy, Vol.2. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Murnane, R. J., Willett, J. B., & Boudett, K. P. (1999). Do male dropouts benefit from obtaining a GED, postsecondary education, and training? Evaluation Review, 23, 475-504.

Steurer, S., Smith, L., Tracy, A. (2001). “Three State Recidivism Study”. Prepared for the Office of Correctional Education, US Department of Education. Lanham, MD: Correctional Education Association.

Tolbert, M. (2002). “State Correctional Education Programs.” Washington, D.C.: National Institute for Literacy. http://www.nifl.gov/nifl/policy/st_correction_02.pdf

U.S. Department of Education, Office of Correctional Education (1994). “The Impact of Correctional Education on Recidivism 1988-1994,” Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

ESL in Corrections

ESL in Corrections

Molly Wilkinson and Kenneth Mentor

English as a Second Language (ESL) is the term used to describe English language instruction for nonnative English speakers. Another term used to describe the non-proficient English speaker is Limited English Proficiency (LEP). All prisoners in the U.S. should be able to demonstrate proficiency in English. If not, they must enroll in ESL or LEP instruction. In addition to providing language skills needed in the institution, corrections-based ESL and LEP instruction seeks to provide the learner with the basic language skills necessary to perform adequately in general education classes.

Of the 1.4 million inmates in federal or state prisons, 8% are non-US citizens. The number of inmates with limited English speaking ability is much higher. According to the Federal Bureau of Prisons, 31.7% of inmates held in federal facilities are classified as Hispanic, 1.6% as Native American, and 1.8% as Asian. These numbers vary greatly by state. For example, 53% of New Mexico inmates are Hispanic. New York has the second highest percentage of Hispanic inmates with over 32%. Five other states have Hispanic prison populations of over 25%. Although Spanish is the most common non-English language in prison, the ethnic background of inmates is changing in ways that reflect recent trends in immigration. As a result, we can expect an even wider range of languages in state and federal prisons. Due of a growing number of illegal immigrants, in some cases entire facilities are being filled with non-English speakers. In this case the language needs are so complex that ESL instruction is being supplemented, or replaced, with electronic translation technologies.

Assessing and Teaching